A Gentle Introduction to HVMI

Introduction

Hypervisor memory introspection (HVMI) has been around for quite some time now, and there are several open-source projects utilizing virtual-machine introspection (VMI), one way or another. Generally, existing projects focus on debugging or tracing the execution of a guest VM. In this blog post, we introduce a slightly different approach to memory introspection; live protection of guest VMs. We cover the motivation behind our HVMI engine, how it was conceived, how it evolved over time, and finally, why we made it available for everyone.

Throughout this blog, we assume the reader has some basic knowledge about virtualization technologies (Intel VT-x specifically) and about OS internals (both Windows and Linux), although we try to cover as much ground as possible when it comes to technical details.

What HVMI Is

Memory introspection is the technique of analyzing the contents of a guest VM from outside. The most common way to achieve this is using a hypervisor – running guest VMs are analyzed or introspected by the hypervisor. The CPU context can be viewed, the contents of the physical memory can be observed, and so on. In addition to simply analyzing the state of the VM, the introspection logic, or HVMI (how we refer to it from here on) also leverages the virtualization features provided by the CPU to provide security.

For example, by using the Extended Page Table (EPT) feature provided by Intel CPUs, HVMI overrides the guest OS memory protection policies. HVMI could, for example, enforce a no-execute policy for certain memory areas, and an exploit would fail even if it compromised the OS kernel. In addition to using the EPT to enforce memory access restrictions, HVMI can also use other virtualization capabilities to offer security. It can prevent modification of certain critical resources, such as control registers or model specific registers. Rootkits or exploits that rely on modifying these will fail because HVMI blocks the modifications.

HVMI is not about just advantages; it does have some drawbacks. One of the most important disadvantages of HVMI is the semantic gap – from outside the VM, we see only raw physical memory, with no apparent meaning. To do something useful, we must infer what those memory pages contain. Is it a process structure, is it a stack page, etc. In addition to the semantic gap, providing protection for certain system resources may prove challenging, from a performance point of view. Many legitimate accesses made inside a page that contains a protected structure may induce a severe performance overhead; this makes choosing what structures to protect a very difficult task. Finally, implementing HVMI is often very complex since it often requires reverse-engineering chunks of OS kernel, advanced knowledge about virtualization and, of course, software engineering.

HVMI History

HVMI began as a research idea almost 10 years ago (late 2011). The team initially consisted of only one researcher (yours truly), who developed the initial PoC (simple driver-object protection via EPT, to block the TDL rootkit). Once the blessing from the powers that be was received, more time and effort was invested into this research, and the team began to grow. What was initially very straightforward code capable of protecting a handful of non-paged kernel memory pages on Windows 7 grew to become a beast capable of protecting all Windows versions starting with Windows 7, several Linux distros, and, on each of these, even user-mode processes, from various types of attacks.

HVMI was available as a commercial product in 2017, as part of the SVE package – Security for Virtualized Environments. During this time, it was polished, performance was improved, and several new features were developed. In late 2019, we decided to open-source the technology to make it available for everyone to see, use, play with, and extend with new features and capabilities.

How HVMI Works

In essence, HVMI requires a hypervisor that provides the required API to provide protection. The required API can be explored in the official documentation. Once such an API is provided, HVMI places several types of hooks inside the guest. For example, it can intercept control register 3 (CR3 - the register containing the address of the page-tables used for translating linear addresses to physical addresses) – this way, HVMI intercepts context switches inside the guest. By intercepting, for example, SYSCALL MSR writes, HVMI intercepts and blocks attempts to manipulate the SYSCALL entry point address. Most importantly, it uses the EPT to alter physical memory access permissions, thus overriding and restricting access to certain areas of the guest memory.

General Architecture

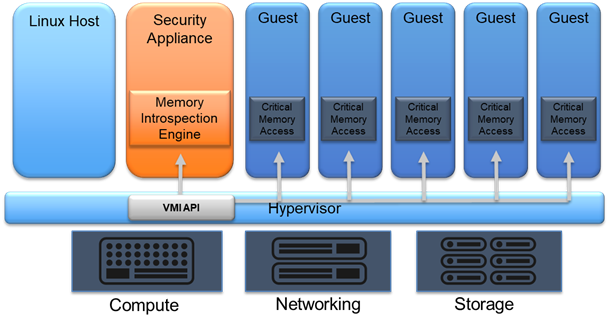

The HVMI engine is a standalone library, self-contained (it has no explicit external dependencies), and can be run in user-mode, kernel-mode, or even VMX root-mode. It is written entirely in C, with small bits and pieces written in assembly. The HVMI engine expects an interface containing several API functions to be exposed to it by whatever integrates with it. In this context, the integrator is a tool that binds the HVMI library to a particular hypervisor which provides a uniform API.

Supported hypervisors include our internally built Napoca Hypervisor, and the well-known open-source hypervisors Xen and KVM. Using the Napoca hypervisor, the HVMI engine runs directly inside VMX root, alongside the HV. In Xen and KVM, the HVMI engine runs as a regular user-mode process inside a special VM (or domain), or even dom0. The general architecture of HVMI is illustrated in the following image:

From a functional perspective, HVMI is an event-driven library. When introspection is enabled for a guest VM, HVMI starts by identifying the guest operating system type, version, to find various important structures inside its memory. This process is asynchronous, meaning that once the initialization function returns, there’s no guarantee that HVMI has finished initialization; some parts of the guest introspection process occur when various events take place (for example, when CR3 is written). Once introspection is enabled, HVMI kicks-in when interesting events take-place within the guest; when a process is created or terminated, when a new memory region is allocated inside a protected process, or when memory accesses take place inside a protected region.

Making Use of HVMI

Although we won’t go into very deep details (yet!) regarding the internals of the HVMI engine, here’s a list of the most important features HVMI exposes:

- The list of loaded kernel mode drivers, with load/unload events;

- The list of user-mode processes, with create/terminate events;

- For processes that are protected, the list of loaded user-mode DLLs with load/unload events, and the list of Virtual Address Descriptors for that process with alloc/free events;

- On Windows, access to the Page Frame Number (PFN) Database;

- On Windows, the ability to parse the object tree (this is currently used to search for driver-objects inside guest memory, but it can easily be extended to handle any kind of object);

As for OS agnostic features HVMI provides:

- Guest hardware registers state query;

- Guest physical memory access;

- Ability to place read/write/execute hooks on physical memory;

- Ability to place read/write/execute hooks on virtual memory;

- Ability to place access hooks on control registers;

- Ability to place access hooks on model specific registers;

- Ability to place access hooks on descriptor table registers;

- Ability to intercept exceptions that take place inside the guest (for example, #PF, #BP, etc.);

- Ability inject exceptions inside the guest;

- Access to swapped out guest memory (by injecting #PF inside the guest);

- Ability to hide certain guest memory contents (reads issued inside the guest will be fed with custom values);

- Advanced instruction decoding and handling (the disassembler used by HVMI provides extended information about the decoded instructions, making information extraction and emulation very simple)

Protection features

The primary purpose of the HVMI engine is to, above all, provide protection. The following list contains the main types of threats HVMI was built to mitigate:

- Binary exploits inside protected processes;

- Code and data injection techniques inside protected processes;

- Function hooks inside protected processes, on designated system DLLs;

- Rootkits (various techniques are blocked, such as inline hooks inside the kernel or other drivers, SSDT hooks, Driver-object hooks, system register modifications, etc.);

- Kernel exploits;

- Privilege escalation;

- Credentials theft;

- Deep process introspection (prevents process creation if the parent process has been compromised);

- Fileless malware (powershell command line scanning).

Start Contributing

We see great potential for the HVMI project, which is why we decided to open-source it and make it available to everyone. Researchers are welcome to clone the project, run it, experiment, and add new features. We also accept pull-requests – if you think your feature is cool enough, be sure to make it available on the main HVMI repo!

Intel is continuously developing new virtualization technologies which make HVMI better and faster. Some of these have already been released, such as the Virtualization Exception (#VE), VM Functions (VMFUNC) and Sub Page Permissions (SPP), and HVMI makes use of them. Others, such as Hypervisor Linear Address Translations (HLAT) have recently been announced, and will make it into silicon in the upcoming years. We are sure that other technologies are yet to come, showing that both hardware vendors and software developers want to invest time and effort to create new virtualization features!

Useful links

- The HVMI project is located at https://github.com/hvmi;

- The documentation is available at https://hvmi.readthedocs.io - it contains both a high-level documentation and the low-level source code documentation, in Doxygen format;

- For any discussions regarding the project, everyone is welcome to join our slack at kvm-vmi.slack.com (you can use this link to join automatically: https://kvm-vmi.herokuapp.com);

- For security issues discovered in the HVMI project, please use the following e-mail address to report them: hvmi-security@bitdefender.com; e-mails must be encrypted using the hvmi public PGP key, which can be found at the end of the post.

-----BEGIN PGP PUBLIC KEY BLOCK-----

Comment: User-ID: hvmi-security <hvmi-security@bitdefender.com>

Comment: Created: 7/15/2020 2:01 PM

Comment: Expires: 7/15/2022 12:00 PM

Comment: Type: 2048-bit RSA (secret key available)

Comment: Usage: Signing, Encryption, Certifying User-IDs

Comment: Fingerprint: 8FA363D0AD6F31067044FF4D6AA85FC4467740F2

mQENBF8O4fkBCADfjTRjJFXASxSm7D8ZOnHmmYh8Achg92P3UcWoYlnLo7rryTZV

7vv1LMwHpDXzbv3Za0vo0vbDtjmDC9PBHBo5CCIPOG0Bp4rhk889VZZoeyWs2sq+

SFfGSDkIeXc5JRXyAHfhyz8rJFVYU72R+0v62DPZLenoBgbFnY6yq5Xc8EMuwKPx

mgpg9J/jdLWy1mBN79ZQrCwp/ZKxBv7TR0quazY9K1WARUplWwVptnYJ0W/THnXe

qF0dggWayr6ASZhmyGZEiQFbkJpMzgCWr49CgjVfw1MXidH8bif9Y2Zsv3ATRNm+

TQMRlAsi+XlqO5Zcx+hnAOna6IRI6vFOli4LABEBAAG0LWh2bWktc2VjdXJpdHkg

PGh2bWktc2VjdXJpdHlAYml0ZGVmZW5kZXIuY29tPokBVAQTAQgAPhYhBI+jY9Ct

bzEGcET/TWqoX8RGd0DyBQJfDuH5AhsDBQkDwkqXBQsJCAcCBhUKCQgLAgQWAgMB

Ah4BAheAAAoJEGqoX8RGd0Dy4kMH/1wnPVqFBXOZcR2CRiWHExbIWwnzfDrYm/tE

ZzSof5QwSFN8DH8hLvNUcbflpkfgB0X8s6RjhCqbpfR/UyWmDNdsRPQ6AUh3aWUk

K5BFdIEQB+Aiv3CWOpIGSDMriKaAyxheuqaNvxTyat75XWvmK7OkkiVZZjx9Pooq

XFYOqSxDZxRwawQYlxXC9GNhXhtD4L8/n5RvB5Lc7coWas0jJKfrh+HTcR1+dybb

14HRBh/BU6P/NIn0quN5Gkukqiym/pR7MbfjfrBNibt1rcu9/sP/BzG0sNUHIxLV

aXczDEcqG7gtzIEHTma40+OIjchlsWKREDPHUryQ7pHcW8oRTJW5AQ0EXw7h+QEI

AL2/tnXRPYX2TEWac9G8bhaWhIoKxh62bQlStp+lG6jGsEGAjonhI+vTRb5I4e7z

bA89dHbt/CSyrngm8e+RbInZ7omVPT/QD+DcF+iV7O7DsUnANKamGSLkKbrSwQ+u

1ywVTVwF+kubNgluvG50tX3OdtSlQTbwZCPjvB6B5ORNq1lwFFuiF6XyG+sUHRBq

9YBUmfGsOS0WSP39Cb/ExGmLw4RnDWQJax7Z8oaKL6QKG3QoEUgP8BdRzgYLHgqH

F4mB5GaEqSK+IhZ3NPdWJbTmbBSRJM3xyCunWg4xCqTAyJw/PrTDGZNWPVFt/LQy

YhfI4GmH3RXO7gaq3ntvrK0AEQEAAYkBPAQYAQgAJhYhBI+jY9CtbzEGcET/TWqo

X8RGd0DyBQJfDuH5AhsMBQkDwkqXAAoJEGqoX8RGd0DyVVoH/0KmyKparR6UrtbD

Lv4eNOI58DypfY4jJ5mR5PWFH4ewPalu8Sw0Pa6ngI554OQ+0G0dYUXVViUCRnpN

TBs32NyOnRWH3vgLoYfhdG7qebO53IYgFwvCDRYWjrDVMgrlmFJIAcdHk1dsZ2mL

SFiM3wVmZeQhMExcDABlub8WItBvLo5QD/JJQ55ZlE/Z2DO7m7oOhsUAolp1W7Yq

72ITifuDrFrmgyq4B+jBqL55nnDDmXrGNrksj5tsgGUyq5tYKbRLYgqQ9lmNyNXE

nibaE27Tr1XnZLzcOMesjEpWBPL3l0Jwxru7pYqA3xWd/8wXZSf9HmJmyoUDXIDy

thGcFZM=

=vBFM

-----END PGP PUBLIC KEY BLOCK-----