Page Fault Injection in Virtual Machines: Accessing Swapped-Out Pages from HVMI

Introduction

Hypervisor Memory Introspection, as its name implies, relies heavily an analyzing guest memory contents in order to infer details about the OS structures or to analyze the behavior of the kernel and applications. This works perfectly as long as only physical memory or resident virtual memory is analyzed (for example, guest page-tables, or non-paged kernel memory). Many times, however, regions of the Windows kernel memory or regions belonging to user-mode processes will not be mapped in physical memory, thus preventing HVMI from analyzing their contents. In this blog post, we will describe how we deal with swapped-out guest memory, in order to ensure HVMI will get a chance to analyze the contents of a memory page even if it is not resident in physical memory: meet the page-fault injection mechanism!

Paging Overview

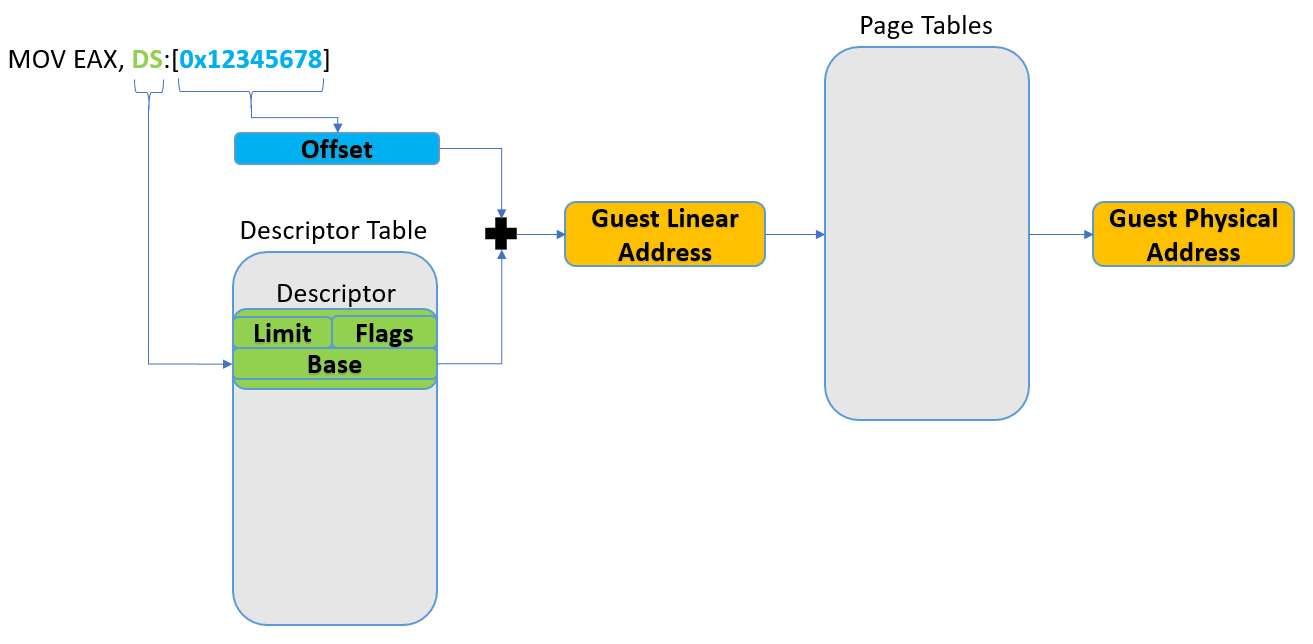

On x86, there are several resources that control virtual to physical address translation. The first stage of a virtual address translation is segmentation. During this step, the guest virtual address accessed by the instruction is added to the segment base used by the instruction, forming the guest linear address. The guest linear address is then translated by the paging mechanism into a guest physical address. The guest physical address is then translated via the EPT to a host physical address, which is then accessed by the hardware. This is illustrated in the following image:

When implementing virtual memory, the operating system builds both the descriptor table and the page tables which are responsible for address translation. While the descriptor table is global, hence its name, Global Descriptor Table, or GDT for short (albeit there can also be Local Descriptor Tables as well, but this is not the subject of this blog post) and is the same for the entire system (including all the processes and the kernel), the page-tables used by the processes are different for each process. This means that, for example, svchost.exe and calc.exe use different sets of page tables for their guest linear to guest physical address translation. Therefore, the same guest linear address will translate to different guest physical addresses in different processes.

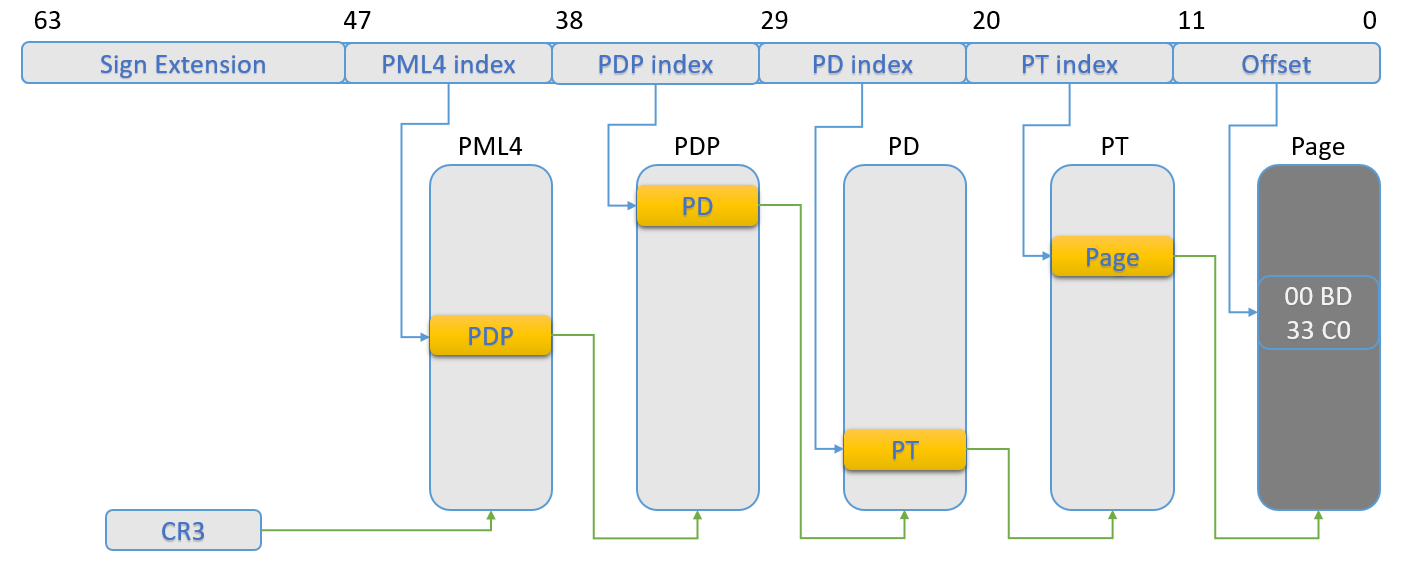

How are different page-tables used for different processes, though? The CPU always uses the page-tables pointed to by the CR3 register for the translation. When a thread is scheduled for execution on a physical processor, the kernel will load the CR3 with the base address of the page-tables belonging to the process which owns the thread. Each page-table is 4096 B or 4 KB long, and each entry is 8 B long (4 B on legacy 32-bit paging). The CPU will first translate the virtual address to a linear address, using segmentation, and then it will use the resulting linear address as follows (assuming 4-levels 64 bit paging):

- Page Map Level 4, or PML4, will be the starting page-table for translation, and its address is the one in CR3;

- Bits 47:39 from the linear address are used to select an 8 B entry inside PML4, which is the Page Directory Pointer, or PDP;

- Bits 38:30 from the linear address are used to select an 8 B entry inside PDP, which is the Page Directory, or PD;

- Bits 29:21 from the linear address are used to select an 8 B entry inside PD, which is the Page Table, or PT;

- Bits 20:12 from the linear address are used to select an 8 b entry inside PT, which is the physical page address;

- Bits 11:0 from the linear address are used as an offset inside the physical page.

The paging steps are better illustrated in the following image:

Page Faults

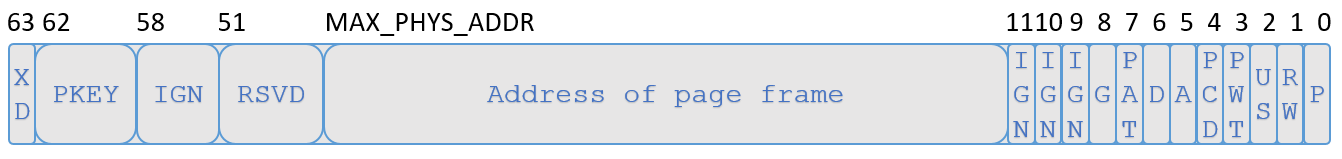

Each page-table entry has a well defined structure, and several bits have special meaning. While translating addresses, the CPU interprets these bits in order to see how it should proceed with the translation. First, let’s see what control bits are present inside a page-table entry:

As we can see in the image above, there are several control bits, but only some of them are interesting to us right now:

- Bit 0 is the Present bit; this indicates whether the entry is valid or not. If the bit is 0, the current entry is invalid, the CPU will stop the page-walk, and it will generate a #PF;

- Bit 1 is the Read/Write bit; this bit indicates whether the range mapped by the current entry is read-only (the bit is 0), or read/write (the bit is 1); in order for a page to be writable, this bit must be set to 1 in all page-table levels;

- Bit 2 is the User/Supervisor bit; this indicates whether the region mapped by the current entry belongs to the kernel (the bit is 0), or the user (the bit is 1); in order for a page to be user-accessible, this bit must be set to 1 in all page-table levels;

- Bit 5 is the Accessed bit, and it is set by the CPU whenever a page translated through that entry is accessed;

- Bit 6 is the Dirty bit, and it is set by the CPU whenever the page translated through that entry is written;

- Bit 63 is the Execute Disable bit, which controls whether the region of memory translated through the entry is executable or; for a page to be executable, the XD bit must be 0 in all page-table levels;

Looking at the list of control bits listed above, we can already infer some conditions that would cause the CPU to generate a #PF:

- The Present bit (bit 0) is 0;

- The Read/Write (bit 1) is 0, and there is a write access to the page;

- The User/Supervisor (bit 2) is 0, and there is user-mode access to the page;

- The Execute Disable (bit 63) is 1, and there is an instruction fetch access to the page.

In order to properly communicate the cause of the #PF, the CPU will save an error code on the stack when delivering the exception. This way, the operating system kernel can quickly determine what the cause of the #PF is, and it can take measures. If, for example, the #PF is caused because a page is not present in physical memory, the kernel can check whether the page is present in a swap file, and if so, it can read it into the physical memory, it can modify the page-table entry by marking it valid, and it can restart the instruction that triggered the #PF in the first place. If, for example, the page accessed by the instruction is invalid (it’s not mapped at all), the kernel could, for example, kill the process. The layout of the #PF error code is fairly straight forward, and the bits most important to us are:

- If bit 0 inside the error code is 0, the #PF was caused by a non-present page; otherwise, it was caused by a present page;

- If bit 1 inside the error code is 0, the #PF was caused by a read access; otherwise, it was caused by a write access;

- If bit 2 inside the error code is 0, the #PF was caused by a supervisor (kernel) access; otherwise, it was caused by a user access;

- If bit 3 inside the error code is 0, the #PF was not caused by a reserved bit being set inside a page-table entry; otherwise, it was caused by a reserved bit being set in a page-table entry;

- If bit 4 inside the error code is 0, the #PF was not caused by a an instruction fetch; otherwise, it was caused by an instruction fetch;

For example, an error code of 0x3 (bit 0 and bit 1 set) would mean that the page-fault was triggered by supervisor code writing to an already-present page, meaning that the page is present, but is marked as read-only inside the page-tables. Likewise, an error code of 0x4 (bit 2 set) would indicate a #PF caused by user-code reading from a non-present page.

Accessing Swapped-Out Pages

Now that we have a good understanding about the paging mechanisms on an x86 CPU, it is time to answer the following question: we can always access guest physical pages, but why can’t we always access a guest linear page? The answer should be pretty obvious: because that page may not be present inside the physical memory - it is marked as not-present (bit 0 - the Present bit - is 0) inside the page-tables. This means that its contents are located somewhere on the storage device, but not inside physical memory. How can we work around this inconvenience, if we really have to inspect the contents of a swapped-out page?

The naive approach would be to somehow access the page on the storage device, but this would come with several drawbacks. First, you’d need a way to access the VMs storage device from the HVMI, which is very difficult, since - remember - we operate completely outside the VM. In addition, you’d have to know the structure of the swap file in order to locate the desired page. Performance is also an issue, since accessing the storage to read swapped-out pages may induce some noticeable performance impact.

A better approach would be to wait for the page to be read naturally by the guest. This can be done by polling the guest memory, to see when the page is brought back inside the physical memory. Even better, the page-tables can be monitored against writes, and when the page-table entry translating the page we wish to read is written, the physical page address can be retrieved, and the physical page can be read. However, this has a great disadvantage: there is no guarantee that the page will ever be accessed again.

What if we’d convince the guest OS to swap in the desired page…? We could do this by executing an instruction inside the guest which would access the page. But executing instructions in guest may be difficult (as we will see in a future blog-post - agents injection inside the VM), so we need a better approach. Luckily, Intel VT-x allows for event injection inside the VM, including exceptions such as #PF. Therefore, we can simply inject a #PF inside the guest, and let the guest kernel handle it as if it was generated naturally by instruction execution.

#PF Injection

When injecting #PFs inside the guest VM, there are several questions that must be answered.

First of all, we need to classify the #PFs into two categories: user-mode and kernel-mode faults. User-mode faults are injected to access user pages, while kernel-mode faults are injected to access kernel pages. It is important to make this distinction, because while in user-mode the OS is always willing to accept #PFs, inside kernel, some #PFs may lead to a bug-check or a panic - for example, if a #PF is generated while at a high IRQL, or when accessing non-paged memory.

Secondly, in the case of user-mode #PFs, we need to know what process the page belongs to - remember, each process has its own virtual address space, its set of virtual pages and its own set of page-tables. The #PF must be injected inside the correct process, to ensure that the correct page is swapped in. This means that the #PF must be injected only when the correct process is running. Luckily, when HVMI determines that it needs to swap in a certain process page, it is already running in the context of the desired process (it rarely needs to inject #PF for a different process while introspecting another process). However, if a #PF needs to be injected for another process, HVMI could force a VM exit, such as an EPT violation, to happen in the target process, and it could then inject the #PF, knowing that the correct process is running.

Finally, we must be careful with the #PF error code, since it indicates to the OS what actually triggered the #PF. When injecting a #PF for a user page, bit 2 must always be set, indicating a user-mode access. Since we inject a #PF to swap in a non-present page, bit 0 must always be 0. Since we are generally interested in only reading the swapped in page, the bit 1 of the #PF error code should be 0, indicating read access.

Now that we are able to inject the #PF for the target page, we need a way to know when the page is actually swapped in. The best way to do this is by leveraging the EPT hooks: simply mark all the page-table entries that translate the target page as non-writable, and wait for the OS to modify them. When the target page is swapped in, the OS will have to store the new physical address the target page is translating to in the page-tables, and when it will do so, an EPT violation will be triggered. At that point, HVMI will see that a page-table entry is being modified, and it will decode the written value, thus determining the physical address the target page is being mapped to. HVMI can now already read the target page, as it’s in physical memory already, and it can proceed with inspecting it.

Example

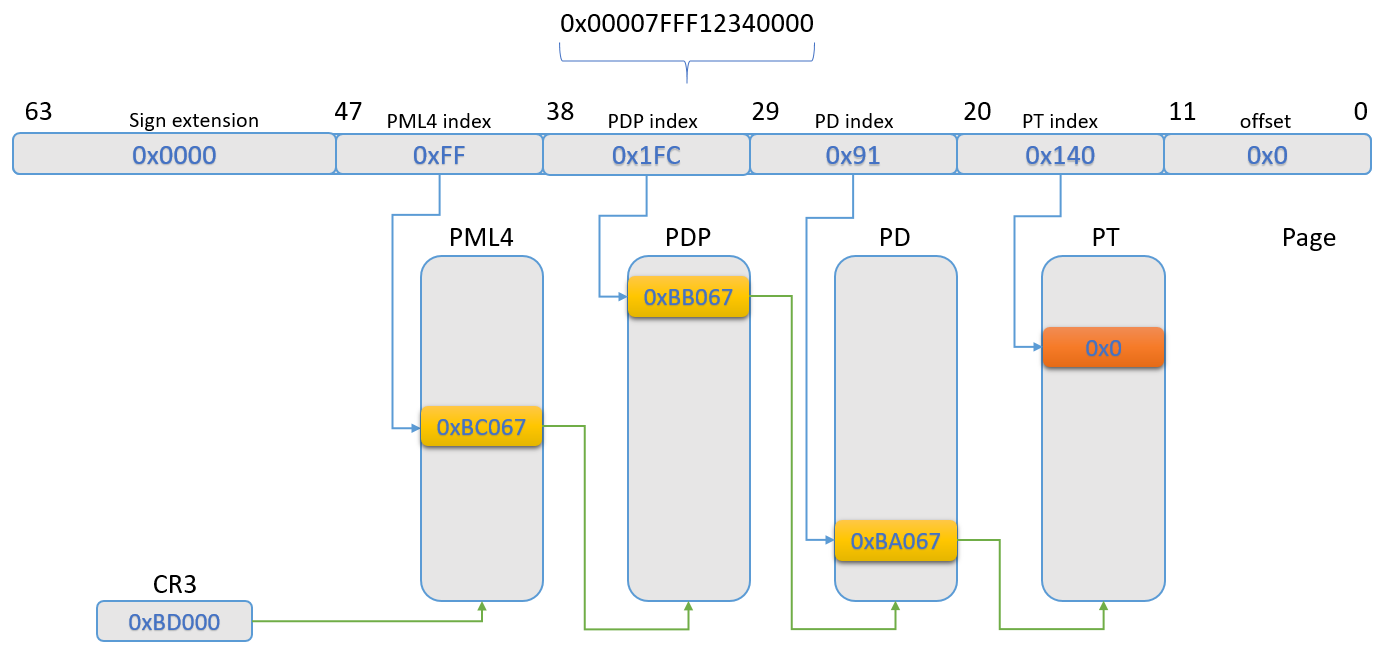

Let us now assume that we wish to read the virtual page 0x00007FFF12340000 inside the process test.exe, which has a CR3 value of 0xBD000. Let’s split this virtual address, in order to extract the indexes inside the different page-table levels:

- The PML4 index is represented by bits 47:39, which are

0xFF; - The PDP index is represented by bits 38:30, which are

0x1FC; - The PD index is represented by bits 29:21, which are

0x91; - The PT index is represented by bits 20:12, which are

0x140; - The byte offset inside the accessed page is represented by bits 11:0, which are

0x0(and are of no interest to us for this example).

Let us now take a look at the page-table entries that translate this virtual address:

Looking at the image above, we can see that all page-table entries are present, except for the last level, the PT entry. The entries inside the PML4, PDP and PD are 0xBC067, 0xBB067 and 0xBA067, respectively, which indicate present, writable, user-accessible, accessed entries. In contrast, the PT entry is 0, which means that the entry is not present, and accessing it would lead to a #PF.

In order to properly read the indicated virtual page, we will do the following (we assume that we are already in the context of the correct process):

- Place EPT write hooks on each page-table entry used to translate the virtual address:

0xBD000 + 0xFF * 0x8,0xBC000 + 0x1FC * 0x8,0xBB000 + 0x91 * 0x8and0xBA000 + 0x140 * 0x8(of course, note that the actual EPT hook is placed on the entire page-table, but we’re only interested in these particular entries); - Compute the #PF error code that needs to be delivered - in this case, we are dealing with a non-present user-mode page, so the error code will be

0x4; - Inject the actual #PF;

- Resume the guest execution, which will lead to the #PF being delivered and handled.

At some point, the guest kernel will handle the #PF by reading the actual page from the disk, and by mapping it to our virtual address. This will be done by updating the page-table entries accordingly - in our example, only the last level, the page-table entry, is marked invalid, so the kernel will simply modify it to contain the newly allocated physical page which contains the read data. Let’s see how the events unfold:

- The kernel allocates a new physical page - let’s say

0xABCD000, where it will read the content of the virtual page; - The kernel will write the newly allocated physical address + the control bits inside the PT entry, for example, using the following instruction:

MOV [rsi], rcx, where thersiregister contains the virtual address of the PT entry, and thercxregister contains the new PT entry, which will be, for example,0xABCD007, which means that the page is present, writable and user-accessible; - This instruction will generate an EPT violation, as it writes to the EPT-hooked PT entry;

- The EPT violation gets delivered to HVMI, which, seeing that a PT entry is being modified, will decode the instruction, and determine what value is being written - in this case, the written value is the one in the

rcxregister, which is0xABCD007; - Now that HVMI has the written value, it knows that the virtual page

0x00007FFF12340000is being mapped to the physical page0xABCD000, and it can now access it in order to analyze its contents!

Looking at the example above, you might ask why is it needed to EPT hook all page-table levels, since only the last one contains the invalid entry? The answer to this is quite simple: the entry could be invalid at any level. For simplicity, we assumed only the PT entry is invalid, but in reality, the PML4 entry could be invalid, so the chain of events would be more complicated, as more EPT violations would be generated until the final page is actually mapped. In addition, even if a page-table entry is valid, nothing prevents the kernel from remapping it and making it point to another valid entry. In order to cover all these cases, HVMI intercepts accesses to all page-table levels, ensuring that any translation modification is handled properly.

Reading swapped-out memory in HVMI

Inside HVMI, reading swapped-out memory is implemented in the swapmem.c file. The main function is IntSwapMemReadData, which simply receives the input arguments, such as the CR3 of the target process, the virtual address and the size (which can be greater than a single page) to be read, and once all the data is available, it will call a user-supplied callback. Swap-in events are being handled by the IntSwapMemPageSwappedIn function, which is called by the HVMI core when a virtual page is swapped in. The following is a very simple example of how the command line of a process is read using this mechanism:

IntSwapMemReadData(pProcess->Cr3,

gva,

readLength,

SWAPMEM_OPT_UM_FAULT,

Context,

0,

IntWinGetProcCmdLineHandleBufferInMemory,

NULL,

&pProcess->CmdBufSwapHandle);

A breakdown of all the arguments is as follows:

pProcess->Cr3is the CR3 of the process owning the read pages; this is required - as shown previously - so as to inject the #PFs inside the correct process;gvais the guest linear address of the command line in memory, and this is where the read will start at;readLengthis the number of bytes to read; as mentioned, it can be anything from 1 byte to several megabytes;SWAPMEM_OPT_UM_FAULTindicates that this is a user-mode #PF - therefore, bit 2 inside the #PF error code must be set; other options can be used, for example,SWAPMEM_OPT_NO_FAULTwould indicate that a #PF should not be injected, and instead, we should just wait for the page to be naturally swapped in by the guest;Contextis an optional context that will be passed to the callback that will be invoked once all the data has been read in memory;0is an optional context tag; if not 0, the swapmem mechanism would automatically free the suppliedContext;IntWinGetProcCmdLineHandleBufferInMemoryis a callback that will be invoked oncereadLengthbytes have been read starting atgva;NULLis a pre-injection callback, that can be invoked before actually injecting the #PF; it is not used in this case;pProcess->CmdBufSwapHandleis a handle to the swap object; this handle can be used to keep track of the request, or to simply cancel the read request.

While reading the command line of a process is already a clear example of how the #PF injection is used, there are several other cases where memory is read using this mechanism, since pages may be swapped out:

- Reading user-mode modules (headers, exports, etc.);

- Reading both user-mode or kernel-mode paths;

- Reading user-mode stacks;

- Reading swapped-out portions of the kernel;

In addition, IntSwapMemReadData also handles memory that is already present in physical memory, so the developers need not do any kind of checks before calling this function. If the entire memory range is already present in physical memory, the callback would be called directly. Otherwise, a #PF will be injected for each page that is not already present in physical memory. More details about this API can be found in the HVMI documentation and Doxygen documentation.

Conclusions

Accessing guest virtual memory is critical to any VMI application. However, many times, virtual memory may not be present in physical memory, especially when introspecting user-mode processes. In order to overcome this challenge in HVMI, we developed a mechanism which allows us to convince the operating system to map swapped-out pages in physical memory by injecting #PFs. In order to know when the page has been swapped in, we use EPT to monitor the guest page-tables for writes, and once the page-table entries translating the swapped page are written, the instruction is decoded, and the physical address is decoded. Once the physical address is determined, the contents of the page can be accessed easily. The #PF injection allows us to read both user and kernel memory, which is critical for providing proper protection to the guest VM kernel and applications.